Archer St. John & The Little Company That Could by Ken Quattro 2006

Foreword

It was Mark Hanerfeld’s tribute to Kubert’s Tor in Alter Ego #10 way back in 1969 that first tipped me to St. John comics. Kubert I knew, of course, but who was this caveman Hanerfeld raved about? I eventually acquired 1,000,000 Years Ago #1(the unwieldy real title of Tor) and came to know he spoke the truth. Over time, various St. John books drifted in and out of my collection. While they never attained the consistent quality across the board that E.C. had, there was a determined streak of originality running through the line. I began seeking out information about the company and was surprised by much of what I learned. Particularly regarding Archer St. John himself. The man and the company are virtually inseparable and I found I couldn’t tell the story of one without also telling about the other. My research led me down paths, and a few cul de sacs, I never expected.

Certain aspects of the St. John story may be familiar and have been told in detail elsewhere. Those facts I give only cursory attention. Whenever feasible, I tried to direct the reader to the other sources.

This article isn’t intended to be the last word on the St. John story, but hopefully it is a starting point.

Ken Quattro

kquattro@comcast.net

Acknowledgments

In addition to the specific sources cited within this article, I’d like to give special thanks to: Matt D. Baker, Michael Barnes, Jerry Bails, Jerry Beck, Roger Carp, Gene Colan, Arnold Drake, Ric Estrada, Michael Feldman, George Hagenauer, Joe Kubert, Joan Howard Maurer, Leon Maurer, Stephen O’Day, Trina Robbins, Fred Robinson, Jerome Lafayette St.John, Dr. Michael Vassallo, Jim Vadeboncoeur Jr. and Ray Zone. A special thank to Roger Jeffries for his uncommon generosity.

Cited sources (other than the individual comic books) are noted by the yellow digits which link to the Endnotes page following this article. Additional sources are located on that page as well.

The Brothers St. John

He shouldn’t have become a comic book publisher.

If his mother had her way, Archer St. John would have been a military man, an officer in the Army or Navy. That was expected of the second son. That was the tradition in her family.

“…Archer, which had been my mother’s maiden name.” 1

The fact was, that although Archer would found the publishing company that bore the family name, he lived in the shadow of a more famous sibling. His older brother, Robert, who should have become a clergyman if he had obeyed his mother’s wishes, instead became a world famous war correspondent and author. Despite his peripheral role in Robert ‘s 1953 autobiography, This Was My World, it is through the words of his brother that we can glean most of the known details of Archer’s early life.

Title page from This Was My World by Robert St. John (1953)

The St. John family was solidly middle class when they moved to suburban Oak Park, Illinois from Chicago in 1910. Archer, two years younger than Robert, would have been six at the time. The father, John (Strangely, Robert never named his parents in his memoir. Their names come from another source.), was a chemist, a pharmacist in today’s parlance, who moved his family to the upscale town to escape the encroaching squalor of the big city and to open a second drugstore. The children, however, quickly learned that they fell into the lower caste within the privileged community. They lived “south of the trolley tracks” and a world apart from those on the north side, like their family physician, Dr. Hemingway (who had a son named Ernest…).

The St. John’s financial situation worsened when young Archer was in an automobile accident. He was thrown from the vehicle and his skull was crushed on a manhole cover. His mother, Amy, who had been a nurse prior to marriage, insisted that the surgeon allow her to assist in the operation that saved Archer’s life.

Out of necessity, she returned to nursing when her husband died from cancer in 1917. In the aftermath of his death, the family lost both drugstores.

St. Alban’s Episcopal Academy in Sycamore, Illinois (circa early 1900s).

[photo courtesy of The Joiner History Room, Sycamore Public Library, Sycamore, IL]

Robert left school to get a job and eventually joining the Navy to fight in World War I. Meanwhile,his mother remarried and Archer was sent off to boarding school at St. Albans Episcopal Academy in Sycamore, Illinois. Robert’s narrative doesn’t give any further details of Archer’s schooling. The next time he is mentioned is in the account of their coinciding encounters with the Capone mob.

Bullets and Ballots

By the early 1920s, both St. Johns had become journalists. Robert was employed as editor and writer with the Cicero Tribune, while Archer had started his own newspaper in a neighboring town, the Berwyn Tribune. The older brother had continually crossed Al Capone with a series of revealing articles about his nefarious activities. Archer incurred Scarface’s wrath when he announced a special edition of his paper would expose Capone’s planned infiltration into Berwyn’s government by the manipulation of the upcoming mayoral election. On the same day, April 6, 1925, Robert was beaten severely in broad daylight by Capone and several of his thugs, while Archer was kidnapped off a public street and ‘taken for a ride’. Later that day, he was released, too late to publish his expose’, too late to influence the voters.

“He had been handcuffed, blindfolded, and kept in a shack somewhere, then taken to a woods and set free, “wrote Robert,“When he finally found his way home, his wrists were cut and he talked incoherently.” 2

The newspaper accounts of the attacks tell a slightly different story.

With Robert’s book as a guide, I asked George Hagenauer, comic historian, crime expert and good friend, to conduct searches of contemporary Chicago newspapers for me. Surprisingly, the Chicago Daily Tribune of April 7, 1925, told a somewhat different story than Robert. Although the two versions agreed on Robert’s assault, when it came to Archer’s attack they diverge.

Noting that the incidents were“…said to be co-related,” the Tribune reporter

Detail from Chicago Daily Tribune article (April 7, 1925)

Confused eyewitness accounts are quite common and nothing in Robert’s book supports this story. If Archer was shot, it seems logical that Robert would have mentioned it. The Tribune article further states,” …St. John staggered and several men dashed out and pulled him into the car. Hiding behind the closed curtains, they dashed away and St. John hasn’t been seen since.”4

The most sensational coverage of the incident occurs in the April 7th edition of the Chicago Herald and Examiner: Spread over seven columns, “EDITOR VANISHES IN SHOOTING MYSTERY“, screamed across the top of the front page.

Seven column headline from the Chicago Herald and Examiner (April 7, 1925)

(Robert had remembered a similar headline in his book, but he attributed it to the Chicago Tribune. As often happens, his memories of over a quarter century earlier were faulty.) The accompanying story, however, made the same error as the Tribune in naming the Berwyn editor as “Arthur“. One detail reported here that is missing from the Tribune account was that Archer had been assaulted on Ogden Avenue just outside of Berwyn. The supposed shooting, “…was believed to be a sequel to an attack in Cicero earlier in the day.” 5

Soon after these incidents, Capone purchased the Cicero Tribune in order to silence Robert. Faced with an obviously impossible situation, Robert quit and went into partnership with Archer on the Berwyn paper. “Archer was a good businessman, but it was a shoestring operation.” That required them to perform every aspect of publishing from the writing and editing to setting type. “But we had no capital and had to go to extreme measures to keep our creditors from closing us out.” 7 Column heading from Chicago Herald and Examiner (April 7, 1925)

Still, the brothers found time for things besides work.

“…Archer and I would go off for an evening to Chicago’s Near North Side and forget payroll and publication problems by taking part in semi-professional plays.”

“Archer played some major roles in the Little Theater productions.” 8

Eventually, “Archer and I won our Berwyn campaign, for Capone finally gave up his ideas of a westward expansion and even stopped his sniping of us.” That battle won and now bored, “There were also financial reasons for moving on,” Robert wrote, “As long as Archer and I had been content to live on black coffee and cigarettes, we had been able to get along…”. 9 In 1927, Robert leaves the Berwyn Tribune for a job as managing editor of a paper in Rutland, Vermont. At this point, Archer departs from Robert’s memoir.

“Model Railroading for Fathers and Sons”

Sometime in the early 1930s, Archer resurfaces in New York, as advertising manager of Lionel Trains Corporation. Seeking details, I contacted Roger Carp, senior editor of Classic Toy Trains Magazine. “His was an executive position, “ wrote Carp, “editing its magazine for hobbyists, placing ads in national publications and overseeing production of the annual consumer and dealer catalogs.”

St. John’s editorial hand can best be seen in the Model Builder magazine Lionel began publishing in January, 1937. The magazine was a mix of toy train layouts, true railroad stories and ads for Lionel products.The beautifully colorful covers were illustrated by topnotch artists such as Gordon Ross and John Rogers and were obviously influenced by concurrently published comic books.

Model Builder v. 1 #1 (Jan.-Feb. 1937) Model Builder v. 1 #3 (May-June 1937)

cover by Gordon C. Ross cover by Gordon C. Ross

While the content was comprised mainly of photographs, over time St. John apparently realized the potential of the comic book form. Indeed, he often employed future comic book artists. Years before he would draw “The Pie-Faced Prince of Pretzelburg” in Jingle Jangle Tales, George Carlson was doing spot illustrations for Model Builder. George Carlson illustration from

Model Builder v.1 #6 (Nov.-Dec. 1937)

A page entitled, “Toots ‘n Whistles” in the October 1942 issue, featured artwork by August M. Froehlich. Froehlich was a frequent Classics Illustrated artist of such issues as “Black Beauty” and for Fiction House’s “Auro, Lord of Jupiter” that ran in Planet Comics.

In the February issue of the same year, a “W. Kremer” illustrated the true story of a young heroine named Kate Shelly. This has been identified as very early work by longtime Harvey artist, Warren Kremer. It should be noted that Kremer eventually worked for the St. John comics line a decade hence.

“Kate Skelly” page by Warren Kremer (?)

from Model Builder v. 6 #31 (Feb. 1942)

Carp’s email to me concluded, “Lionel and other toy firms were prohibited by the federal government from using “strategic materials” (metal and rubber) to make trains and other toys after mid-1942. So Lionel had little to sell except items to the military. It cut back on its sales staff and advertising, so perhaps St. John was already gone–or was looking for another source of income…”

Archer may have left Lionel (for the time being at least), but a clue to his immediate future career may be found near the beginning of the 1942 edition of the Air News Yearbook. 10 This book, a compilation of airplane photos and facts culled from Air News magazine, contains a simple cryptic dedication:

Dedication page of Air News Yearbook (1942)

The Flying Cadet Mystery

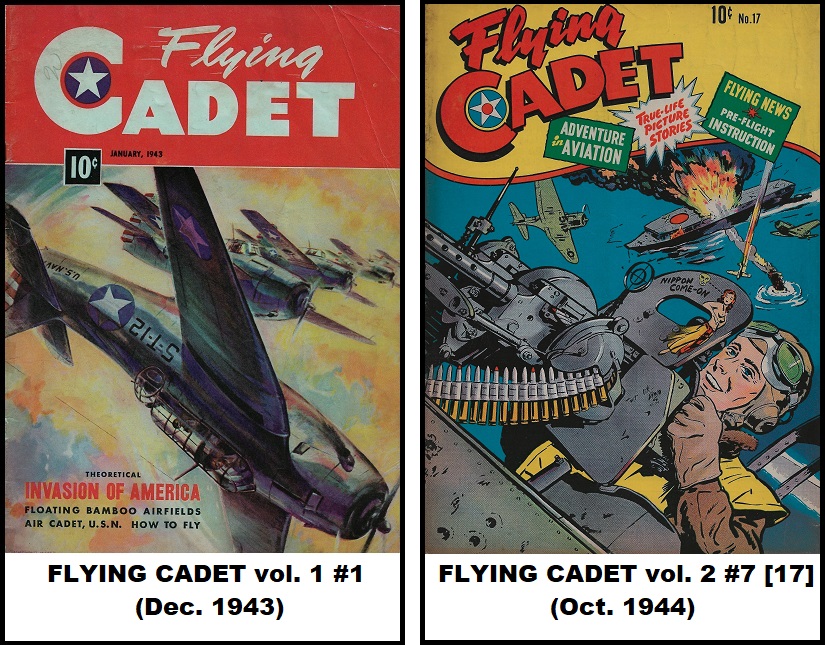

The first verifiable connection of Archer St. John to comic books appears on the contents page of Flying Cadet #1 (Jan. 1943). St. John is listed as editor and eventually, in the final issue, #17 (Oct. 1944), he’s named as the owner as well.

Flying Cadet was a unique book, part comic, part magazine and aimed at, “…young men, between the ages of 15 and 19, accurate and clarified information that will be helpful to them in preparing themselves for aviation careers,” its stated purpose printed in issue #1. In many ways, it was quite similar to Model Builder under St. John.

Flying Cadet #1 (Jan. 1943)

cover by L. Meinrad Mayer

The magazine portion was chock full of black and white photos and illustrations of airplanes and young pilots. The comic book section, which falls in midway through the book, is basically instructional material. In its premiere issue, the one identifiable artist of the comic book section is L. Meinrad Mayer, who also provided the cover painting. Mayer was an illustrator with a list of credits such as the Saturday Evening Post, but undoubtedly the fact that he was the primary cover artist for the Lionel trains catalogs starting in 1936 made him a known quantity to St. John.

Flying Cadet began looking more and more like a magazine soon after it’s debut. It increased slightly in size and virtually all of the covers were photos. Gone was any attempt at fiction, with all of the features now informational. L. Meinrad Mayer became the art editor in addition to his duties as the primary artist. The only other readily identifiable artist was Eric Sloane, a noted illustrator who handled the remaining art chores.

With its final issue, #17 (Oct. 1944), Flying Cadet underwent a dramatic change and was now more comic than magazine. Once again at standard comic book size, the change is obvious from the cover: a pure line drawn depiction of an airplane gunner.

Bare-breasted woman cover on

Flying Cadet #17 (Oct. 1944)

The majority of the book is filled with straight up comic book features, like Buzz Benson (by Maurice Whitman), Grease Pan Gus, a humor strip, and Lt. Lela Lang, a female bomber pilot story written (and drawn?) by George Kapitan. Kapitan seems to have had a hand in most, if not all, of the stories in this issue. Meinrad Mayer and Eric Sloane were still around, but now with a greatly reduced workload.

Flying Cadet was also the publisher of record for several other comic ventures. American Air Forces #1 (Sept.-Oct. 1944) was published by Flying Cadet before William H. Wise took over with issue #2. This followed the same comic/ magazine format as Flying Cadet.

“Buzz Benson” story from Flying Cadet #17 by Maurice Whitman and George Kapitan

Most intriguing of all are the several issues of Harry “A” Chesler’s Dynamic Comics that were published by Flying Cadet. At the least, issues 8, 9 and 15 had Flying Cadet in their indicia, as does Punch Comics #12.

What does this all mean?

Most likely, Flying Cadet was a surrogate publisher, established for its allotment of paper. During World War II, as comic historian Michael Feldman explained to me, “It was something like 75% of your consumption by weight the previous year. There was a maximum per publishing entity, so the more companies you had the more paper you could apply for.” This was a tactic employed most famously by Martin Goodman at Timely. Chesler apparently used the Flying Cadet name for the same purpose, even after the Flying Cadet comic had ceased publication.

Since Chesler and his editor Phil Sturm were in the military sometime in 1942-43, he may have left Archer St. John as managing editor or possibly as some sort of business partner. There are other clues that suggest a link between Chesler and St. John.

Several Chesler shop alums became prominent at St. John. The owner’s statement that appears in Dynamic #15 (July 1945), names Dana Dutch as the editor of this issue. Dutch, who was also a writer for Chesler from approximately 1944 to ‘46, later went on to be the main writer of St. John’s romance comics line. Worth mentioning also is Joe Kubert’s apprenticeship at Chesler and subsequent time in that shop as an artist, circa 1945.

The covers of Chesler’s comics routinely pushed the limits of taste with their gory and risqué subject matter. St. John’s Flying Cadet #17 takes a step in that direction with a cover portraying a topless woman on the side of a machine gun, foreshadowing by several years Chesler’s Dynamic #20 and Punch #20 with similar semi-nudity. At this time, few if any other comic book publishers took such daring chances. While such boldness could be coincidence, it seems unlikely.

(It should be noted that St. John’s editorial office for Flying Cadet was in the Graybar Building at 420 Lexington Avenue, while Chesler’s editorial office was located at 163 W. 23rd Street. Although this doesn’t invalidate a link between the two, it does show that St. John enjoyed a certain amount of autonomy.)

As St. John was starting his own imprint, he filled his comics with reprints, notably in Authentic Police Stories and Crime Reporter, from Chesler books. In 1953, St. John again dipped into the Chesler well with his one foray into a super-hero comic, Zip-Jet, which featured Rocketman reprints from Chesler’s Punch Comics. According to comic historian Jerry Bails, Chesler also packaged comics for St. John.

At first glance, Archer St. John and Harry “A” Chesler seem to be a very odd couple.

Chesler was a Runyon-esque character. “He’d come in wearing a hat on the back on his head with a watch chain in his vest,” Gill Fox recalled to Jim Amash in Alter Ego #12, “He reminded me of a fight promoter, and he smoked a cigar.” 11 Gus Ricca’s cover to Dynamic #12 is most likely a nod and a wink to that description of his boss. A demanding employer, many of his former artists referred to his studio as a humorless ’sweat shop’. Chesler’s infamous ’frugality’ led to his being derisively nicknamed “Harry Chiseler” behind his back.

Dynamic Comics #12 (Nov. 1944)

with Gus Ricca caricature of Chesler

Conversely, few comic book publishers, if any, enjoyed the respect and admiration of his employees like St. John. Intelligent, gentlemanly and generous, Archer was unique among his peers. John Benson in his wonderful exploration of St. John’s romance comics, Romance Without the Tears, quotes Archer’s son Michael, “My father bent over backwards trying to be kind and good to people and I think a lot of people appreciated his largess, and benefited in many ways from him.” 12

It’s always risky assuming too much in the murky, early years of comic book publishing. Comic packagers, of which Chesler was one of the most prominent, left their fingerprints everywhere and St. John’s connection to Chesler may be totally incidental. All of this taken into consideration, the Chesler-St. John link is deserving of further inquiry.

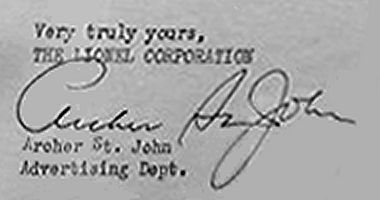

A Flying Mouse, The Friendly Ghost and Funny Men

A pesky interval of several ‘mystery years’ passes from the time of Flying Cadet #17 in October ‘44 and the first comics published under Archer St. John’s own name. It is likely that St. John wasn’t involved in the comic book industry during this period. A document dated December 14, 1944, written and signed by Archer on Lionel Train letterhead exists, wherein he indicates that he is working in that company’s advertising department. Apparently, Archer was now the company’s business manager. He left Lionel soon after, in early 1945. What he did at this point has yet to be determined.

Archer St. John signature on letter dated December 14, 1944

Vince Fago, who eventually worked on Little Audrey for St. John, once told interviewer Jim Amash of a lunch conversation he had with Archer in which, “...He told me he had $400,000 and didn’t know much about publishing but he had the money.“ 13 Presumably, this conversation accord as St. John was getting into the business, sometime around the end of W.W.II. In terms of comic book history, this was just after the so-called Golden Age and at the beginning of what easily can be called the Genre Age. The super-hero dominated comic books were waning in popularity and giving way to a variety of different genres: humor, Western and especially, crime.

Archer St. John was well aware (or well advised) of this, as he never met a genre he didn’t like. Or publish.

Humor was first. The earliest comics of his eponymous company (indeed, the indicia credits Archer St. John solely and not yet St. John Publishing) were reprint books of comic strips from the United Features Syndicate (UFS) stable.

Probably the first book published under his imprint, Comics Revue #1 premiered sometime in 1947. Although the Overstreet Price Guide lists a publication date of June, no date can be found in the comic itself. 14 The entire issue is devoted to reprints of Charlie Plumb’s Ella Cinders. Some, if not all, of the strips reprinted are from 1942-43 continuities, which leaves opens the possibility that the comic book was printed even earlier than the June ’47 guess in Overstreet.

Succeeding issues reprinted UFS stalwarts Hap Hopper, Iron Vic and Gordo. Jane Arden and Gladys Parker’s stylish gal Mopsy firstappeared in Pageant of Comics in September ‘47 before getting their own St. John titles.

Comics Revue #1 (1947)

cover by Charlie Plumb (?)

Mopsy was the most successful of the UFS features for St. John. She not only appeared in 19 issues of her own title, a long run by St. John standards, but also as a back-up page in some of their romance comics. Spunky and sexy, Mopsy was an independent single girl far ahead of her time. Parker’s unique drawing style set Mopsy apart from the predominately male drawn cheesecake in other comics. She apparently began producing original stories for the comic books early in the title’s run, including the paper doll pages that were included in most issues.

As an aside, Mopsy #12 (Sept. 1950) contained the first comic art of future Atlas/Marvel artist Joe Sinnott on Trudi, a 5 page backup story.

Mopsy #1 (Feb. 1948)

cover by Gladys Parker

Somewhat later, long running Tip Top Comics, another United Features product, spent some time at St. John before being acquired by Dell, as did Fritzi Ritz and her niece Nancy. The timing of the St. John publication of these 3 titles coincidentally allowed them to be the host to some of the earliest comic book appearances of Charles Schulz’s Peanuts.

The fortuitous (for St. John) strike by the Terrytoons animators in 1947 seems to have been key in the production of his first comics containing new artwork.

The New Rochelle, New York based animation studio was notoriously cheap by industry standards and in 1947, its animators went on an eight month long strike. During that time, either the licensing agreement with Timely comics ran out or was somehow voided by the strike. In any case, the last Terrytoons properties produced by Timely were dated Summer 1947, while the first St. John Mighty Mouse (#5) appeared with an August ‘47 cover date.

Two views of a matchbook used by Terrytoons to promote their comics. (circa late 1940s)

Whereas the Timely Terrytoons books were produced in-house under the editorship of Vince Fago, the St. John comics had art by Terrytoons animators such as the legendary Jim Tyer, J . Conrad (“Connie”) Rasinski and Art Bartsch, acknowledged by some to be the creator of Mighty Mouse. Bartsch drew many of the covers for the Terrytoon’s books as well as the Mighty Mouse stories. He is even slyly inserted as a character in issue Mighty Mouse #12 (Aug. 1949) called the Great God Bartsch. The Terrytoons license proved to be fairly profitable for St. John as various Terrytoons characters appeared under their imprint over nearly the lifespan of the publisher.

Mighty Mouse Comics #5 (Aug. 1947)

Art Bartsch cover

The success of the Terrytoons comics evidently led St. John to expand his licensed product base. The characters of another New York based second-tier animation studio, Paramount Pictures/ Famous Studios, made their comic book debut in September 1949 in Casper, The Friendly Ghost #1.

This comic carries the somewhat historic distinction of not only being the first venue to name Casper (not even his film appearances had yet gotten around to it), but it was the first time Baby Huey appeared in any medium. Drawn by animator Marty Taras, later a Harvey mainstay, this comic appearance hit the newsstands months before Huey’s screen debut on March 3, 1950. St. John gave up The Ghost (sorry…) with issue #5 (Aug. 1951). Interestingly, Little Audrey not only saw her first comic life at St. John, but lingered there a bit longer than the other Paramount characters until issue #24 in May of ’52.

Casper, the Friendly Ghost #2, pg. 1

(Feb. 1950)

The licensed characterizations of notable comedians were also part of the St John line. It should be noted that the humorous depiction of real life comedians was unique at the time. National didn’t take the plunge with the Adventures of Bob Hope until February 1950. Judy Canova and Milton Berle were similarly immortalized in that year. St. John led the (admittedly small) pack with the publication of Abbott and Costello #1 dated February 1948.

This title was not only the first of their three comedy team books, it was also the longest running, ending with issue #40 in September 1956. A probable reason for the success of this book (other than the continuing popularity of the comedy team itself) was that much of the art in the early issues was by the talented husband and wife team of Eric Peters and Lily Renée (Wilhelms) Peters. Renée (who only used her first and middle names professionally) was the star of the team and best known for her work at Fiction House on such features as Senorita Rio. While Renée also illustrated the St. John one-shot teen comic, Kitty, and a few stories for its romance titles, it was Abbott and Costello that provided the main showcase for her artwork.

Abbott and Costello #1 (Feb. 1948)

cover by Charles “Pop” Payne

A common practice at Fiction House that Renée knew well, was the advantages of ’Good Girl’ covers. Not surprisingly, her Abbott and Costello covers often featured an attractive young woman along with the comic’s stars. This obviously eye-catching device became the standard for the genre and was followed by Owen Fitzgerald on the Bob Hope comic and perfected by Bob Oksner on the Dean Martin and Jerry Lewis book. Eventually, a young Mort Drucker took over the majority of the art chores on Abbott and Costello. In an odd bit of placement, there was even a Son of Sinbad backup story in issue #10 (Aug. 1950) by Kubert, which appeared six months after the one and only issue of that comic was published.

Abbott and Costello #2 (March 1948)

cover by Lily Renée and Eric Peters

Already a veteran comic book artist at a very young age, Kubert saw the new company as an opportunity, “I came to him (St. John). He was a publisher and I was an aspiring packager.”

Part of Kubert’s ‘package’ was lifelong friend, Norman Maurer. Maurer had been working as an artist for Lev Gleason on such series as the Little Wise Guys in Daredevil Comics. With him on board, Kubert suggested a potential comic for which Maurer was uniquely qualified.

In 1945, Maurer met Joan Howard, daughter of Moe, the mop-haired leader of The Three Stooges. Joan and Norman married in 1947 and that same year, Maurer negotiated an agreement with Moe, his brother Jerome (Curly) and Larry Fine. The contract, dated May 28th, entitled Maurer and the Stooges to 5 percent of the net profits from any comic book sales based on their movies. 15

Norman Maurer at work on a

Three Stooges page

[photo used with permission of Joan Maurer]

The Three Stooges #1 (February 1949), contained stories adapted from their Columbia films, Uncivil Warriors and Hoi Polloi, written and drawn by Maurer. Kubert chipped in with a Mark Montage detective story.

The second issue in May of ‘49 continued with the same format. Despite the talent involved, the comic was canceled with this issue and the Stooges comic book franchise would languish for some time.

The Three Stooges #1 (Feb. 1949)

cover by Norman Maurer

Splash page from “Uncivil Warriors” Splash page from “Hoi Polloi”

Norman Maurer art Norman Maurer art

October of ‘49 saw the premiere of Kubert’s brief venture into romance comics, Hollywood Confessions #1. A virtual one-man effort (Kubert had a hand in every story, although Hy Rosen penciled at least one.), this comic tried a unique approach to involve the readers. A house ad invited the readers to submit true stories that would be illustrated for future issues. There was even a cash award of ten dollars offered. This title had a curious evolution. It lasted one more issue under Kubert’s aegis, than became Hollywood Pictorial with issue #3 in January 1950 (with Matt Baker art). This change was short-lived as it morphed into (Western) Hollywood Pictorial, a Western movie magazine containing all photos and no artwork, with issue 4 in March. This was St. John’s first tentative movement into magazine publication, foreshadowing the direction of the company several years hence.

Hollywood Confessions #1 Hollywood Pictorial #3 Hollywood Pictorial #4

(Oct. 1949) (Jan. 1950) (March 1950)

It should be noted that the house ad in Hollywood Confessions had a return address for Jubilee Publications, although the indicia names St. John as publisher. Jubilee was also the publisher named in the Stooges comics. the reasons why St. John used this surrogate company name is unknown. The prior reasoning which was a dodge around war mandated paper shortages, no longer applied. Michael Feldman explained a likely scenario:

“…shifting titles from publishing name to another was a strategy to keep each company below a tax level plateau. A company earning $100,000 might have to pay at a 30% rate, but two earning $50,000 only paid 20%, and so on.”

House ad for Jubilee Publications

Hollywood Confessions #1 (Oct. 1949)

More puzzling is his one-title publishing imprint, Blue Ribbon,which fronted the like-named comic of rotating humor and romance genres.

Other Jubilee titles also appeared in 1949. Among them was Northwest Mounties, Western Bandit Trails and World’s Greatest Stories, a Classics Illustrated– type comic aimed at a younger audience. As with many St. John comics of the period, this title lasted only two issues. The first issue adapted Alice in Wonderland and the second, Pinocchio. Both were nicely drawn in an animated cartoon-like style by an artist who simply initialed all his work, “EC”. Comic art sleuth Jim Vadeboncoeur, Jr. has offered the opinion that it was the work of Ellis Chambers.

To add to the confusion, Jubilee appears sporadically in indicias at least until 1953 (i.e. Whack #2, Dec.1953).

World’s Greatest Stories #2 (May 1949)

cover by Ellis Chambers (?)

Late in 1949, two new Kubert creations were published with cover dates of February 1950. Secret Missions was a comic book version of Admiral Ellis Zacharias’ book and radio show of the same name that dealt with his career as a military intelligence officer.

The other comic, the aforementioned Son of Sinbad, was Kubert’s take on the swashbuckling offspring (and namesake) of the legendary sailor. Kubert’s Sinbad looked very much like Douglas Fairbanks Jr. who, not so incidentally, starred in the 1947 film, Sinbad the Sailor.

Secret Missions #1 (Feb. 1950)

cover by Joe Kubert

Two of the title character’s run-of-the-mill stories are elevated by Kubert’s dynamic and rapidly maturing artwork, while the third Sinbad story looks to be a Carmine Infantino effort with a Kubert assist. The issue is filled out by a Matt Baker-esque, but probably not Baker, “Omar of the Magic Robes” backup tale that wouldn’t have been out of place in one of St. John’s romance titles.

Fine artwork notwithstanding, neither this comic nor Secret Missions made it past the first issue. However, the lone Kubert Son of Sinbad story in Abbott & Costello #10 suggests that at least one more issue of that title had been in the offing.

Son of Sinbad #1 (Feb. 1950)

cover by Joe Kubert

It is likely that poor sales weren’t the sole reason for the demise of these comics. The Kubert/ Maurer partnership had run into an insurmountable obstacle: the Selective Service Administration intervened when it drafted Kubert in 1950. This event effectively curtailed not only his contributions to the fledgling publisher, but apparently also those of his partner Maurer. More than two years would elapse before either creator’s work would appear again in a St. John comic.

The third comedy team, Stan Laurel and Oliver Hardy, made their comic book premiere in Laurel and Hardy #1 in March 1949. This series was drawn by Reuben Timmons (nee Timinsky), who was yet another St. John artist best known for his animation work, with a career extending from Betty Boop to A Charlie Brown Christmas. This short lived title ran only 3 issues in this incarnation.

Laurel and Hardy #1 (March 1949)

cover by Reuben Timmons

Then There Were Giants

It didn’t take St. John long to realize a cruel fact of comic book publishing: Unsold books were returned and the publisher had to find a way to recoup at least some of his losses. As others had before him, Archer St. John decided to repackage these remaindered comics by removing their covers and binding several of them together in new covers. He certainly wasn’;t the first publisher to do this, but as was his style, he put a new spin on it.

The common practice of the time was to bind two or three comics into one package. St. John’s 1948 volume of A Treasury of Comics consisted of 16 remaindered comics! Further, the package was contained within bookboard covers. Archer even wrote a preface to this book that not only describes its purpose, but gives some insight into the man himself:

“This volume has been compiled for the laughter and enjoyment of boys and girls; and is dedicated to those artists and writers who, with skill, imagination and good taste, are producing wholesome entertainment and amusement for millions of readers; adding dignity, scope and influence to this new technique of story-telling, the continuity of dialogued illustrations, called comics.

In this book are sixteen comics magazines which, in the opinion of the editors of this publication, are representative of the best stories of the year, worthy of preservation and of a place alongside Moby Dick, Tom Sawyer and Treasure Island, on library shelves.“

—Archer St. John

This statement could stand as St. John’s vision for his new publishing company. It’s doubtful many of his contemporaries would have as eloquently described their offerings as a, “new technique of story-telling, the continuity of dialogued illustrations, called comics.” Fewer still would have dared to compare them to literary masterpieces.

This prodigious Treasury was produced for two more years and in the meantime, St. John began to package smaller remaindered books. Notable among these was 1950’s Little Audrey Yearbook which contained 8 comics and the aptly named Giant Comics Edition, which varied content and size from issue to issue. Eventually, remaindered copies of Authentic Police Cases, Mighty Mouse and the various genre comics were repackaged into giant 100 page issues as well.

Little Audrey Yearbook (1950) Giant Comics Edition #12 (1949)

cover by Matt Baker

The Third Man

Beginning the same month as Abbott and Costello, Authentic Police Cases was St. John’s first venture outside strip reprints or the humor genre. Apparently trying to cash in on the then popular crime comics, St. John’s entry in the market was, at first, nothing more than a vehicle for reprinted Chesler comics. The first issue (February 1948) featured a cover by Paul Parker and on subsequent issues, Bob Lubbers, the second Fiction House mainstay to work for St. john.

It was the third Fiction House regular that would have the greatest impact on the fledgling publisher. Beginning with Authentic Police Cases #6 (Nov. 1948), the covers and much of the interior art would be drawn by Matt Baker.

Authentic Police Cases #6 (Nov. 1948)

cover by Matt Baker

Archer St. John had apparently decided to build his company upon the skills of just a few creators. Likely this decision was financially driven. A small publisher like St. John wouldn’t have the resources to put together an in-house ‘bullpen’. Still, he proved to be an uncanny judge of talent. Building upon his inventory of licensed material and reprinted Chesler shop artwork, St. John’s selection of Kubert, Maurer and Baker gave him a potent artistic triumvirate.

By the time Baker’s art began appearing in Authentic Police Cases (in actuality, his first St. John comic work was in Northwest Mounties #1 and the cover to Crime Reporter #2, both October ’48), he had already established a reputation for depicting beautiful women while working for various publishers. However, the venerated status that Baker has attained today obscures the realities of the time period.

Matt Baker and Archer St. John

in front of Grauman’s Chinese Theater

[photo used with permission of

Fred Robinson & Matt D. Baker]

“He was the first Black artist to work in mainstream comics,” notes legendary writer Arnold Drake, “Which convinces me that St. John got him at a bargain rate…but any publisher in the industry could have gotten Baker for that same bargain price based on race. Since they didn’t do it and St. John did do it, which marks Archer as a liberal.”

St. John, or one of his editors, went even further to find other artists to help Baker on Authentic Police Cases.

Starting with issue #15, Enrico (“Martin”) Bagnoli’s art began gracing the interiors. In a style heavily influenced by Alex Raymond, Bagnoli worked long distance, very long distance. Based in Italy, the artist would receive and send his assignments via registered mail. Jim Vadeboncoeur, Jr. in Alter Ego # 32 tells the complete fascinating story of Bagnoli and the other Italian artists assisting him, such as Antonio Toldo and Antonio Canale. 16

Page from Authentic Police Cases #18

(April 1953) art by Enrico Bagnoli

Baker’s importance to St. John would only increase over time. With Kubert and Maurer gone, he became the major artistic force at the company. Whether the subject was Westerns, crime or war, Baker was dependably solid. His most lasting impact, though, would come in a genre for which he was perfectly suited.

Romance and Lust

St. John early on realized the potential of the romance comic boom and began publishing its first comics of that genre in 1949. Teen-Age Romances #1, dated January of that year, established Baker immediately as the source of the de facto “look” of their line. Baker not only drew all of the line drawn covers for the romance titles, he penciled most of the interior stories.

It is noteworthy that several of the early issues of Teen-Age Romances were of a slightly larger size, had photo covers and were partially filled with the articles, ads and columns befitting a magazine. It seems that once again St. John employed the tried and true format that he had used on Flying Cadet and that Timely was currently using on Miss America Magazine. Apparently the experiment didn’t work as it soon went back to being a pure comic book.

Teen-Age Romances #1 (Jan. 1949)

Matt Baker cover.

Out of all the comics published by St. John, the romance comics were routinely its most successful. Over the life of the company, as many as 20 different romance titles were published under their imprint. The distinctive storylines of the romance comics led John Benson to state in his book that the strong-willed heroines and the guilt-free tone of the stories were a conscious theme suggested by Archer St. John himself and manifested by the ubiquitous writing of Dana Dutch.

Cinderella Love #25 (Dec. 1954) Teen-Age Romances #43 (May 1955)

Matt Baker cover Matt Baker cover

It should be noted, though, that Baker, as well as the other romance artists and writers worked under the editorship of Marion McDermott (who was also editor of Authentic Police Cases and Fightin‘ Marines). In a publisher sorely lacking an identity, she maintained consistent quality in each of her comics, in all genres.

Starting with Baker as her primary artist, McDermott’s books featured work by a small, but talented, group of freelancers. Apparently, she brought out the best in each.

“…I walked into St. John’s Publications and was lucky enough to meet romance editor Marion McDermott, who loved the way I drew pretty girls and gave me an assignment on the spot, ” artist Ric Estrada wrote to me. He fondly recalled the “Lovely Marion McDermott,” who assigned him, “…scads of stories for Teen-Age Temptations, Teen-Age Romances and others. She praised the fashionable dresses I drew on my girls as opposed to the humdrum styles by other artists.” Gene Colan, who was hired by McDermott to work on Fightin’ Marines, described her as being, “very very nice,” and that he remembered, “…trying different techniques while working for her.”

Baker himself blossomed under McDermott. As art director of her books, Baker’s artwork became noticeably more mature , more illustrative, particularly his exquisite romance covers. Surely this was the pinnacle of his career.

Crime Reporters

Was it a secret wish by a publisher that had once been a crime reporter to be the star of his own comic book? I can’t say for sure, but the title did keep popping up on some early St. John publications…

Pageant of Comics #2 Crime Reporter #2 Authentic Police Cases #8

(Oct. 1947) (Oct. 1948) (Aug. 1950)

cover by Russell E. Ross cover by Matt Baker cover by Matt Baker

Romance and Lust

In 1950, St. John published a digest-sized comic with a single book-length story and called it a Picture Novel. Illustrated by Baker and inker Ray Osrin, in many ways It Rhymes with Lust was the prototype of the modern graphic novel. A detailed synopsis of the book’s plot can be find in Alberto Becattini’s terrific ’Baker of Cheesecake’ article in Alter Ego #47. 17

The credited pseudonymous author, “Drake Waller“, was in fact the writing team of Arnold Drake and Leslie Waller. I contacted Mr. Drake for details about the creation of this historic book and although he has told this story before, I was taken with the vividness of his words and the detail of his recollections:

It Rhymes with Lust (1950)

with art by Matt Baker and Ray Osrin

“In 1949 (published in 1950) Leslie Waller and I created “Picture Novels”. We were both at school (he at Columbia and I at NYU) on the GI Bill of Rights. To augment the $20 the government paid us weekly, we collaborated on some comic book stories. Pulps were being driven off the market by a combination of paper-back books and comics. Les and I sold a couple of Western tales to Ziff-Davis.

As we worked with the comics form, we reasoned that for the ex-GIs who read comics while in the service and liked the graphic style of story telling, there was room for a more developed comic book–a deliberate bridge between comic books and book- books. That was the idea we took to St.John.

We were prepared to make an oral pitch. But about 3 A.M. (I did my best work in those early hours) the morning of D-day, I set out to demonstrate the idea physically.

I took a comic book and folded it in half. Then I drew a two-page layout of a faked story, “One Man Too Many” and pasted it into that folded comic. After which I drew a cover: a nasty guy with gun in hand who’s just discovered his woman in another man’s arms. The fact that it was mounted on that folded comic demonstrated how easy the transition would be for a printer already set up to produce comics.

My drawings have always been crude but clear. They demonstrated the idea more than adequately. (I have the yellowed remains of those layouts.) I also came up with the logo that would adorn the cover: a paintbrush and a pencil crossed over a book cover and the letters PN, for Picture Novels.

What we planned was a series of Picture Novels that were, essentially, action, mystery, Western and romance movies ON PAPER. “Lust” would have made a good Joan Crawford or Barbara Stanwyck film (both often played beautiful-but-treacherous women. And “Lust” was about one such.).

We had never worked with St. John before this. But the grapevine said that he was an independent publisher who took chances on new ideas and was prepared to give the innovator(s) a piece-of-the-action. Also, Les and I were convinced that the mainstream publishers (DC, Marvel and Dell) would never share a copyright or a piece of the profits with the creator.

St. John proved to be as good as the rumor. The art, by Matt Baker, was great…The whole thing shaped up as a fine first effort. The trouble came when it was time to market it.

Panel from It Rhymes with Lust

art by Matt Baker and Ray Osrin

This new-sized product needed special placement on the newsstands and in the shops. You had to convince the public– and more than that, the distributors and retailers– that this was a new idea that would soon sweep the market. There would be no space on the stands for this one odd-ball-product. (Actually, St. John released two. The second one, a mystery yarn, was a disaster, both story and art. Les and I had nothing to do with it.)”

Most likely, Drake is referring to the The Case of the Winking Buddha. Printed in black and white, the artwork of former Caniff assistant Charles Raab illustrated a story by pulp writer Manning Lee Stokes. Despite Drake’s critique, Raab’s art was solid and very reminiscent of his work on the Kerry Drake and Charlie Chan comic strips.

Also in 1950, St. John published two digest-sized Western comics: Slash-D Doublecross and two issues of Midget Comics (subtitled Fighting Indian Stories). Unlike “Lust” and “Winking Buddha“, neither of these books was conceived as a full length novel, rather, they were traditional comic stories reformatted to digest size.

Page from The Case of the Winking Buddha

with art by Charles Raab (1950)

Case of the Winking Slash-D Doublecross (1950) Midget Comics #1 (Feb. 1950)

Buddha (1950)

Drake continued, “I don’t think there is much question that It Rhymes with Lust was the first graphic novel. It wasn’t a stumbling, accidental creation. Les and I knew exactly what we set out to create. The fact that it was essentially a ‘B Film’ on paper, rather than the more sophisticated products that came 25 years later and called themselves ‘Graphic’ speaks to the change in the readership over those years. The sons and daughters of the veterans who went to school on the GI Bill were a very different market than the one that Les and I dealt with back then. I have no idea what the first Picture Novel would have been had we had that broader, deeper audience.”

Meanwhile…

At the same time St. John was experimenting with various comic formats, he was also branching out into other publishing ventures.

In January of 1950, St. John purchased a venerable Canadian magazine entitled Magazine Digest. Similar in size and concept to the far more successful American Readers Digest, this became St. John’s entry into “legitimate” publishing. Magazine Digest had little in common with the comic book side of Archer’s company, except for a shared address and the presence of Marion McDermott as Art Director.

Magazine Digest (Dec. 1950) Trouble Shootin’ Man (1950)

[Readers Choice Library #14]

Hoping also to cash in on the burgeoning paperback market, St. John established the Readers Choice Library in the same year. This line specialized in three genres: mysteries, Westerns and sexy potboilers. Apparently, the line lasted until sometime in 1951 when it too met the fate of most of St. John’s ventures and faded away. Archer, however, never gave up on either the digest size or the magazine market.

The Eagle and Banner

A quick digression here, to consider the origin of the familiar St. John bald eagle with banner logo.

Until 1951, the only corporate designation on the covers of St. John’s publications were the letters ANC, which noted the distributor, American News Corporation. Late in that year, a diamond containing both the ANC and StJ monograms appeared briefly. (An even less used symbol of a ‘swollen’ St. John appeared on a few comics as well.) Finally, in the February 1952 dated comics, the eagle and banner flew for the first time.

(Dec. 1951)

Over time, the logo became simpler, more stylized. The choice of the eagle is symbolically understandable. Not only did it represent strength and American patriotism in a very patriotic era, but it also recalls that Archer St. John’s first venture in comic book publishing was an aviation book.

I can’t say for certain that Archer was a coin collector, but if so, it would confirm what was most likely the visual inspiration for St. John’s symbol.

1839 ‘Gobrecht’ silver dollar 1856 ‘Flying Eagle’ cent

From 1856-58, the United States mint issued the classic ‘Flying Eagle’ cent. The eagle on It, in turn ,was a derivation on the bird found on the reverse of the ‘Gobrecht’ Silver Dollars of 1836 to 1839. While not an exact duplicate, the St. John eagle is a close kin.

Kate and Matt

Given Matt Baker’s identification with drawing beautiful women, It is somewhat ironic that his most enduring St. John character didn’t find ‘life’ in a romance comic, but in a war book.

The U.S. engagement in the newly declared Korean War police action spawned St. John’s anthology war comic, Fightin’ Marines #15 (#1)(Aug. 1951). That first issue had a Baker cover and artwork on Leatherneck Jack and Ralph Mayo illustrating a story of a heroic pilot. Over time, the comic would host artwork by Carmine Infantino, Mort Drucker and Gene Colan who would take over the art chores on “Jack”.

Fightin’ Marines #15 [#1] (Aug. 1951)

cover by Matt Baker

“Leatherneck Jack” page by Matt Baker “Leatherneck Jack” page by Gene Colan

from Fightin’ Marines #15 [#1] (Aug. 1951) from Fightin’ Marines #7 (Aug. 1952)

Interestingly, while St. John Publishing was going to war with the Red Chinese in the pages of Fightin’ Marines, Archer’s brother Robert was being accused of being a Communist sympathizer.

Robert was a high profile author and broadcaster by this time and had been named in the controversial and very influential 1950 publication, Red Channels, along with 150 other entertainers and writers. 18 Many of those named in this pamphlet had become blacklisted and Robert himself moved to Switzerland as a consequence.

Click on above image to read

Robert St. John’s Red Channels entry.

Fightin’ Marines #2 (Oct. 1951) featured the first story of a comely waitress/cook at a military base canteen, the aptly named Canteen Kate. Kate was the epitome of a “Baker girl”– sassy, perky and wholesomely sexy.

Panel from Fightin’ Marines #2 (Oct. 1951)

First appearance of Canteen Kate by Matt Baker

This well-meaning “Bombshell from Brooklyn” invariably became involved in situations that were rife for disaster. Frequently it involved her boyfriend, the hapless Private Al Brown.

Case in point was a story in Fightin’ Marines #4, “Tailor Maid”, in which Al complains to Kate that his issued uniform was too small. Kate resolves to fix that problem and after several attempts to get a new uniform legitimately, she ‘borrows’ some material from a chemical research laboratory and makes uniforms for her and Al both. Their attempts to hide from pursuing military police are foiled, though, when it turns out that Kate had used an experimental fluorescent material. Al ends up in the brig with Kate bringing him a sandwich and coffee. How Kate always managed to stay out of the brig herself was never entirely clear and in truth, it didn’t really matter.

Fightin’ Marines #4 (Feb. 1952)

[click on image to read the entire story]

Baker must have enjoyed drawing these madcap stories as it resulted in some of his best artwork. Unlike his earlier artwork at Fiction House and Fox, which frequently found Baker using awkward posturing in order to prominently display women’s ‘attributes’, his St. John work was far more subtle and naturalistic. Sure, Kate wore an improbable uniform made up of an apparent man’s khaki shirt cinched tightly at the waist with a web-belt and rolled up khaki shorts, but the cheesecake was lightly done and rarely inappropriate. Inexplicably, the other Marines were, for the most part, oblivious to the sexy bombshell in their midst. This underplayed hand was refreshing and added to the comedic aspect of the comic.

Page from Fightin’ Marines #3 (Dec. 1951)

art by Matt Baker

Canteen Kate had a brief, but busy, tour of duty. She appeared in Fightin’ Marines #2-9, Canteen Kate #1-3 and a final appearance in Anchors Andrews #1 (Feb. 1953). Additionally, versions of All-Picture Adventure #1 and All-Picture Comedy #1 contained remaindered issues of Fightin’ Marines with Canteen Kate appearances. When Charlton took over the Fightin’ Marines title in 1955, it reprinted the first couple of Canteen Kate stories.

Kate herself has become somewhat iconic, to the point that the cover of Canteen Kate #2 was appropriated, ala Lichtenstein, by pop artist John Sheridan for a 1994 painting.

Canteen Kate #1 (June 1952)

cover by Matt Baker

Joe Kubert in the World of 50 (plus) Years Ago

Whether it was by plan or just a happy confluence of events, starting in 1952, St. John became one of the most innovative comic book publishers of its day. This burst of originality and creativity lasted less than two years, but resulted in a memorable legacy.

The comic industry was in a constant state of flux and fortunately for St. John, they were the beneficiary of the Ziff-Davis company’s withdrawal (for the most part) from comic book publishing.

In what was apparently an effort to increase their newsstand presence, St. John purchased the majority of the Ziff-Davis inventory for the bargain price of $50,000. Late in 1952, former Ziff-Davis titles such as Kid Cowboy, The Hawk and Nightmare began appearing under the St. John imprint. Indeed, the only way a reader could tell that it was a St. John and not a Ziff-Davis comic is by the appearance of the eagle and banner emblem on the cover. To add to the confusion, St. John also published a (basically) reprint line under the blanket title of Approved Comics. Ziff-Davis had also used this name in 1951-52 as a surrogate company name on some of their own comics.

The Hawk #4 (Jan.-Feb. 1954)

While this acquisition boosted the size of St. John’s comic line, the company (other than the Baker drawn/ McDermott edited comics) lacked an identity. Most comics of the major publishers had a similar look. St. John’s comics were a potpourri of styles and consistency.

It is only speculation, but perhaps St. John had been watching the success of E.C. with its commitment to quality and the featured status it granted its artists. Treating the artists as individuals had allowed the readers to identify their favorites, resulting in a fanatical following and increased sales.

Archer St. John surely realized this and welcomed with open arms the return of Joe Kubert from military service in 1952. Kubert was to provide the creative spark that the company lacked and most importantly, he left the Army with two concepts that would have a dramatic effect upon the direction and fortunes of St. John. Moreover, the company was doubly blessed: returning with Kubert was his talented partner, Norman Maurer.

The September 1953 dated comics were to be the watershed moment when St. John comics began to develop a personality.

Joe Kubert and Norman Maurer photo from 1,000,000 Years Ago! #1

[with the cover artwork for Three Stooges #1 & 1,000,000 Years Ago! #1]

A Letter from the Publisher

I’d like you, our readers, to meet Joe Kubert and Norman Maurer. Joe and Norm have been friends since childhood. They first met in New York, where they attended the High School of Music and Art together, in 1940. It was here, at the age of thirteen, that they became interested in cartooning. They got their first jobs working for comic books less than a year later. Yes, Norm and Joe have been drawing for comic books for more than thirteen years!

When Joe was sixteen, his parents moved to New Jersey…and he along with them. But both boys remained in close contact with one another…both dreaming of the time when they could write, draw, and produce comic books themselves. They had a single goal: To create the kind of books that you, the reader, wants!It took World War II to separate them, Norm enlisted in the U. S. Navy. While stationed in Los Angeles, California, he was able to continue his work. Norm now makes his home in Hollywood, California.

Joe, on the other hand, made his “new home“ in the U. S. Army. After spending some time in Germany, he came back to take up permanent residence in New Jersey.

The 3,200 mile distance between them did not discourage their lifelong ambition. The years of experience…the hundreds of successful comic strips both had done…are paying off! Now, thirteen years after their first meeting, their aspirations have become reality.

I think that Joe and Norm have created the kind of magazine that you, the reader, will like as much as I do. This magazine is the product of the combination of almost thirty years of experience in this business! But…it’s still up to you! The only way they can produce the kind of magazines you want, is through your letters of constructive criticisms to them. Every letter will be screened and evaluated by both Norm and Joe. Consideration as to content in future issues will be based entirely on letters received from you. (Some of your letters will appear in these books, answered personally by Norm and/ or Joe.) Any and all questions concerning comic books, artists, or writers will be answered.

Their product is in your hands. Norm and Joe have done their work…now…it’s up to you!

Archer St. John

Publisher

With this introduction, which appeared in both 1,000,000 Years Ago! #1 and the revived The Three Stooges #1, St. John welcomed Kubert and Maurer back into the fold. Despite his enthusiasm, it’s interesting that he chose to overlook the previous brief tour of duty the duo had spent at his company. No matter, he apparently was giving them the freedom to spread their wings.

Kubert’s first big idea was a character he created while sailing to Germany on a troop ship in 1951.

1,000,000 Years Ago! #1 (Sept. 1953)

cover by Joe Kubert

“… Tor, as I’ve said before several times, was my incarnation of Tarzan in a cave,” Kubert once told interviewer Bill Baker, ”When I was a kid, when I started having an interest in cartooning, the Tarzan strip by Hal Foster was one that really gave me the impetus to be a cartoonist.” 20

Another indirect, but undeniably important, influence was the artwork of Charles R. Knight. Knight was the premier illustrator of prehistoric life in the early part of the 20th Century and many of Kubert’s depictions recall Knight’s concepts.

Knight passed away on April 15, 1953, just months before 1,000,000 Years Ago! #1 hit the newsstands.

Splash page by Joe Kubert

from 1,000,000 Years Ago! #1

Detail of Tyrannosaurus Rex from

Field Museum mural by Charles R. Knight

[image property of Field Museum, Chicago, IL]

Page from 1,000,000 Years Ago! #1

by Joe Kubert

Whatever the influences, Tor was a brilliant conception. The promise of Kubert’s earlier work was fully realized in this comic. Tor wasn’t merely a grunting caveman, his thoughts and actions were those of a modern man and put him at odds with the more ‘unsophisticated’ of his tribe. He was a Cro-Magnon among Neanderthals.

His first tale not only found him a lemur-like companion he named Chee-Chee, but also defined him as an outsider. A villainous rival named Klar plots to kill Tor, but in their ultimate battle, it is Tor who triumphs by killing Klar. Tor is banished from his tribe and the rest of the series follows him on his adventures. (Whether it was an in-joke or total coincidence, but Mickey Klar was a writer for St. John.)

Tor #3 (May 1954)

cover by Joe Kubert

The backup features in the rest of the comic were the Wizard of Ugghh by Maurer and Kubert’s Little Nemo homage, Danny’s Dreams. The protagonist Danny Wakely, named for Kubert’s newborn son, would ‘dream’ he was a caveman and awaken in a danger fraught, primordial world. Of course, at story’s end he would always find himself back in the modern world. The feature would enjoy the distinction not only of hosting Kubert’s art, but also that of his old studio-mate, the great Alex Toth in his only St. John work in issue #3 (May 1954).

“Danny Dreams” page from Tor #3

by Alex Toth

In keeping with St. John’s promise that the editors would listen to their readers, an interesting page in #3 finds Kubert and Maurer addressing the reader and the concern that there was “some consternation,“ that they, “had totally ignored the belief that an almighty being actually created all past, present and future.“ It’s fascinating to see a subject as controversial as evolution vs. creationism dealt with directly in the pages of a Golden Age comic book. The two assure the reader that they, “…are neither trying to prove or disprove…” any scientific theories about evolution and that, “…your Bible, standard of present-day civilization, is not contested or refuted in anyway.”

Kubert and Maurer deal with evolution controversy in Tor #3.

Tor #4 (July 1954) Tor #4 (Oct.1954)

Making allowances for the typical incongruities such as placing cavemen and dinosaurs in the same era, Kubert’s Tor is a singular tour de force that stands with the greatest in comic book history.

“This was a rich, yeasty time, ” Kubert once told Will Eisner in one of his Shop Talks, “when comic books really instilled the kind of love that I have for this cartoon business.” 21

While Kubert was creating his primordial world, Maurer returned to familiar territory.

The Three Stooges, in their latest incarnation, were Curly-less. Shemp Howard replaced the deceased (January 18, 1952) Curly not only in film, but also in the comic book. Maurer went with a new format for this series, eschewing the film adaptations as basis for the comic’s stories. His drawing style had matured as well, looking more confident and polished.

Three Stooges #1 (Sept. 1953) Splash page from “Bogus Takes a Beating”

cover by Norman Maurer in Three Stooges #1, by Norman Maurer

“I think that Norm was probably one of the few certifiable geniuses in our business,” Kubert told Bill Baker in Comic Book Marketplace #92, “But I think one of the reasons we were able to work well together was because we helped each other — like I say, like a marriage — we helped each other with suggestions, advice, directions, rather than tear each other down, or to try to alter or change the things that we were doing. We kind of propped each other up, which I always appreciated. I miss him. I really miss him.”

The World Through Red and Green Glasses

While stationed in Germany, Kubert had seen magazines that reproduced photographs in simulated three dimensions.

This spark of an idea was rekindled to full flame when he, Norman Maurer and Norman’s brother, Leon, happened to be driving past the Paramount Theater showing Bwana Devil. Written and directed by Arch Oboler, the cheaply made 3-D exploitation film, which promised, “A lion in your lap! A lover in your arms!”, was an immediate success at its November 1952 release and sparked a flood of imitators. According to Leon Maurer, Kubert’s remark upon seeing the movie marquee, “Gee, wouldn’t it be great if we could make a 3-D comic book?”, inspired Maurer to return home and virtually overnight create the printing process that would result in 3-D comic books.

Bwana Devil one-sheet movie poster (1952)

In one long night, Norman Maurer drew the first 3-D comic page entitled, “The Three Dimensional Stooges in the Third Dimension,” to Leon’s specifications. Early the next day, the Maurers waited for the midtown Manhattan Woolworth’s to open in order to purchase lollipops. “…we figured we could get red and green cellophane from lollipop wrappers, “ Norman once recounted in The Three Stooges Scrapbook, “We bought two packages and made a funny pair of glasses which, believe it or not, worked perfectly.“ 22

Leon completed the technical aspects of the job and they took it to Kubert. Kubert in turn produced a panel featuring his caveman, Tor, using the new process. The three then took the pages and the concept to Archer St. John. Initially skeptical, St. John was shocked when he put on the makeshift glasses and viewed the artwork. He bought the concept on the spot and for it received a 25 percent stake in a partnership with the Maurers and Kubert in the American Sterographic Corporation, the company formed to license the new 3-D Illustereo process. For his financial input, St. John also received a six month head start before the process would be offered to other comic book publishers.

St. John house ad promoting 3-D comics.

It was decided that Mighty Mouse provided the best opportunity to promote the 3-D process and production of the book began in secret.

July 3, 1953 was not only the Friday before a holiday weekend, it was also the day the world’s first three-dimensional comic book went on sale. Officially entitled Three Dimension Comics #1, the Mighty Mouse 3-D comic was a financial bonanza. Selling over 1,200,000 copies at 25 cents each, the comic was credited by the 1953 Encyclopedia Britannica Yearbook with being “…the World’s highest circulation periodical to date of issue.” 23 (although this is dubious statistic since Dell alone had several titles selling over one million copies per month.)

Three Dimension Comics #1 (Sept. 1953) [note: a second edition of this comic was published in Oct. 1953, which was slightly smaller in size and with a glossy paper cover.]

Flushed with success, Archer St. John ordered that the entire comic line be converted to the 3-D. Sensing that the new process was merely a fad, Kubert and the Maurers saw the looming disaster such a step could incur and begged St. John to back off his sweeping decision. St. John refused and the production of a full schedule of 3-D comics commenced.

“We took a whole floor of a building and set up an assembly line, “ Kubert stated in a 1989 interview, “I began work on a 3-D Tor and Norman on a 3-D Three Stooges.” 24 The process involved was time consuming, taking as long as one month per book. Acetate cel overlays were opaqued on the back and then placed on top of the line art drawn on Craft-Tint board. A hoard of artists were hired to pencil, ink and paint, including Russ Heath, who traces his first work with Kubert to a Triceratops backup feature in the Tor 3-D. Production commenced on comics as diverse as the humorous Little Eva, The Hawk (a Western) and House of Terror. Each underwent the 3-D conversion; each rewarded with steadily diminishing sales.

House of Terror #1 (Oct. 1953)

cover by Joe Kubert

“Suffice it to say, by the tenth or eleventh 3-D book,” said Kubert, “sales were down to about 19%, so we had to stop publication of 3-D.” 25 The publics attention span was limited and as Kubert and the Maurers predicted, the fad was waning. Complicating the situation, and surely guaranteeing its failure, was the flood of 3-D product coming from other comic publishers. The six month head start that St. John thought he had secured by his contract with American Stereographic was an illusion. One month after the September cover date of the first Mighty Mouse 3-D, Dell put out a 3-D version of Rootie Kazootie and by the end of the year, more than a dozen others had joined the fray.

There was also the further problem of a copyright infringement suit instigated by William Gaines.

According to Leon Maurer, Gaines had conducted a patent search which found a 1936 application (patent #2,057,051) by Freeman H. Owens titled, Method of Drawing and Photographing Stereoscopic Pictures in Relief, which detailed the preparation of a newspaper cartoon for reproduction as a stereographic relief picture. Unknowingly, Maurer had virtually duplicated Owens process.

These are the last two pages of Freeman Owens 1936 patent detailing his

“Method of drawing and photographing stereoscopic pictures in relief.”

Gaines purchased the Owens process from the inventor and proceeded to file infringement suits against all other publishers of 3-D comics, including St. John. The lawsuit was apparently dismissed, but the damage had been done and Maurer lost any chance of patenting and licensing the process to other publishers. Finding humor in an maddening situation, Kubert and Maurer lampooned the entire imbroglio in the first two issues of Whack.

St. John’s debuted of its Mad knockoff in October 1953, as part of the first wave of 3-D comics. Whack’s premise in its first issue was to satirize the comic book industry and St. John in particular.

Each story was framed with a pseudo-St. John cover and lampooned virtually every genre then popular. Joe Kubert, who edited the comic along with Maurer, led off with his take on the hard-boiled private eye, “Ghastly Dee-Fective Comics”, featuring a hero who looked suspiciously like Dick Tracy. In turn, there was the obligatory Western and romance parodies (by Bob Bean?) , a twisted Dave Berg story, “Animated Horror Comics“, that married the unlikely genres of funny animal and horror.

Whack #1 (Oct. 1953)

cover by Norman Maurer

Most fascinating was a tongue-in-cheek look at the Kubert and Maurer shop itself, satirizing the frenzied state that accompanied the production of the 3-D comics.

The second issue, though, took on the more sordid aspects of the lawsuit in “The 3-D-Ts“. It told the story of a comic publisher who is enraged by St. Peter (read that as: St. John) Publications success with their 3-D comics. Mr. Acme (the evil publisher) hires a spy to steal the 3-D process. Meanwhile, another publisher (Gaines?) hires an inventor (Freeman Owens?) to use one of his old inventions to produce 3-D comics, albeit years after the fact. The story ends with a caricatured Archer St. John (in his first and perhaps only appearance within the pages of a comic) beset by an army of lawyers serving him with lawsuits, and resulting in his acquiring a malady diagnosed as “the 3 DTs”.

Page from Whack #2 (Dec. 1953)

art by Joe Kubert and Norman Maurer

(Incidentally, I contacted Leon Maurer and he was unable to remember whether anyone involved with American Stereographic had ever applied for a patent on their process. Despite the “Patent Pending” notation on the cover of all St. John 3-D comics, I was unable to locate a patent application in my own limited patent search.)

St. John, who had gambled all on the 3-D fad, was overstocked with unusable acetate and unsold comics. The ensuing financial losses nearly bankrupted him.

Noteworthy Efforts

Comic history has, to this point, fixated on the 3-D debacle and ignored what was going on in the periphery of St. John Publications.

In June of ‘52, St. John made its run at the horror and science fiction genres. That month, Atom-Age Combat, Strange Terrors and Weird Horrors all debuted.

Atom-Age Combat was a truly strange comic. It was an anthology title that attempted to tap into the twin Fifties fears of atomic war and alien (as in outer space) invasion. The ’War of Wars’ series took place in the far off time of 1987 and starred Captain Don ‘Buck’ Vinson as a commando leader in an atomic war between a NATO-like alliance and The Reds. The other continuing feature was traditional science fiction fare about Earth’s ongoing struggle against an intergalactic enemy.

The third story was reserved for a standard war story set in the contemporaneous Korean conflict. Even the subtitle, “Stranger Than Fiction“ that ran on every cover never really made sense.

Atom-Age Combat #1 (June 1952)

The unremarkable, but serviceable, artwork was rendered by the likes of Bob Bean, Ralph Mayo and Bob Brown. More interesting as a historical artifact of its time than a comic, this mish-mashed title never took hold and drifted along for 5 issues in its original run. Inexplicably, Atom-Age Combat was revived late in the ‘50s under the Fago imprint.

Relatively tame in comparison to many of their more horrific contemporaries, both Strange Terrors and Weird Horrors frequently featured covers by illustrator George Meyerriecks and interior art by the likes of Lou Cameron, John Belfi, Bob Brown, Gus Ricca and an occasional Kubert appearance.

The comics are best remembered, though, for the three covers ( Strange Terrors #4 and Weird Horrors # 6 and #7) by the enigmatic William Ekgren. These covers were unlike anything before and rarely since. In later times, the word “psychedelic” was frequently used to describe them.

Page from Weird Horrors #8 (June 1953)

art by Joe Kubert

Additionally, Ekgren himself remained a mystery. This was his only comic book work and despite the efforts of comic book historians, nothing was known about him. It became something of a small obsession for me to find out what I could about Ekgren and the story of that search is told in my article, “Who is William Ekgren?” (Soon to be published in Craig Yoe’s Modern Arf! magazine.) In brief, I ‘found’ Ekgren along with some amazing images of his artwork, including an unpublished comic cover.

Strange Terrors #4 Weird Horrors #6 Weird Horrors #7

(Nov. 1952) (Feb. 1953) (April 1953)

Although they contained the Comic Code forbidden words of “Horror” and “Terror”, Strange Terrors and Weird Horrors died long before the Code came into being on October 26, 1954. In time, Weird Horrors was replaced by Nightmare, a vehicle for Ziff-Davis reprints, which in turn evolved into the even more innocuously titled Amazing Ghost Stories.

St. John even made a halfhearted venture into the fading super-hero genre with its two issue Zip-Jet. The comic was a reprinting of the Chesler (that connection again…) characters, Rocketman and Rocket Girl. To be accurate, the stories were reworked, the characters renamed (now, collectively called the Zip Jets) and even re-colored. The cover to the first issue, in fact, was actually the splash page of the Rocketman story in Scoop Comics #2 (Jan. 1942).

Originally published in Punch Comics as well as Scoop in the 1940s, and featuring Ruben Moreira artwork, the duo came and went in the early months of 1953.

Zip-Jet #1 (Feb. 1953)

cover by Ruben Moreira

Humor comics were a mainstay of St. John’s repertoire from its beginning and continued throughout its existence. Although there was a long and apparently profitable relationship with Terrytoons, many of the humor titles were short-lived. Titles such as Bingo , Basil, Little Ike, and Lucy, the Real Gone Gal, all lasted a handful of issues.

One worthwhile one-shot was Kid Carrots (Sept. 1953). The creation of Gene Hazelton, it was an oasis of wonderfully frenetic artwork in a desert of look alike efforts. Hazelton, making his one and only foray into comic books, was yet another veteran animator, having worked for Disney, Warner Brothers and later, Hanna-Barbera, where he helped create The Flintstones.

Page from Kid Carrots #1 (Sept. 1953)

art by Gene Hazelton

In the wake of the 3-D bust, a weakened, but persevering company struggled on into 1954. The Kubert magnum opus, Tor, continued for 3 more issues, Maurer‘s Three Stooges lived on for 4 more.

Often overlooked is the fourth comic produced by the Kubert-Maurer shop (outside the 3-D books), Meet Miss Pepper. The April 1954 humor book was a collaboration of Kubert, Maurer and Bob Bean and portrayed the comedic adventures of a pretty, young school teacher. This was an obvious attempt at cashing in on the contemporaneous radio and television series, Our Miss Brooks. As with many St. John comics, the artwork is outstanding. Unfortunately, this rare display of Kuberts talent for humor only lasts one more issue. (Bob Bean eventually became a movie director, and in time, reunited with Kubert as an instructor at his art school.)

Meet Miss Pepper #5 (April 1954)

cover by Joe Kubert and Bob Bean

An anomaly in the Approved Comics title provides one of the true unrecognized gems of St. John’s comics. Daring Adventures (Approved Comics) #6 (May 1954) is the rare exception in that line of reprints, in that it is made up of all new material (despite the assertion in Overstreet). The Robin Hood cover is by Baker and predates by several years his rendition of that character at Quality Comics. Inside, Enrico Bagnoli beautifully illustrated “The Son of Robin Hood,” Edd Ashe handled the art chores on “Devil’s Arena,” and the masterful Bernie Krigstein drew both “Frog Men Against Belzar” and “The Terrorist“.

Daring Adventures #6 (May 1954)

cover by Matt Baker

Page from “The Son of Robin Hood” Page from “The Terrorist”

art by Enrico Bagnoli art by Bernie Krigstein

A quick sidestep here to mention that even some of the ads that appeared in many of the St. John’s comics of this period are worth noting.

Perhaps partially created to find recruits for the army of artists needed to produce the 3-D comics, was the ad by Kubert and Maurer offering comic art lessons at a charge of $1.00 per lesson. It would be fascinating to know if any professional comic artists began their careers by subscribing to these lessons. In any case, it is hard not to notice that this foreshadows Kubert’s art school two decades later.

Then there were the ubiquitous full page ads for Lionel Trains, including a classic one that ran in the 3-D books. It’s not clear if there was some sort of special arrangement between St. John and Lionel, but given Archer’s previous ties to the toy train company, he may have called in a few favors to get them to purchase so much advertising in his comics.

House ad offering art lessons One of the Lionel Trains that ran in

by Maurer and Kubert. St. John’s comics, circa 1953-54.

The Red-Hot Poker

It had the long and somewhat vague title of Special Senate Committee to Investigate Organized Crime in Interstate Commerce, but its chairman, Estes Kefauver had a very specific interest at this time.

Reply of St. John Publishing Co., New York, N.Y.